|

Kiwithrottlejockey

Guest

|

|

« on: May 31, 2009, 01:26:12 pm » |

|

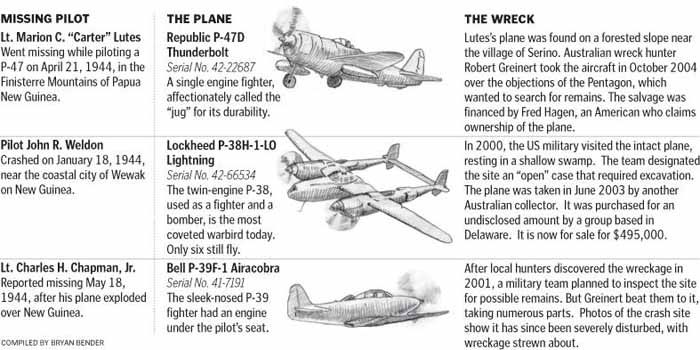

From the Boston GlobeRemains are lost in race for relicsBrisk trade in WWII planes thwarts efforts to recover missing fliersBy KEVIN BARON and BRYAN BENDER - Globe Correspondent and Globe Staff | Monday, May 25, 2009 Australian Robert Greinert finds and restores wrecked airplanes. — Globe Staff Photo/Yoon Byun.ALBION PARK, Australia — To the US military, Carter Lutes, a pilot who vanished in Papua New Guinea in April 1944, is one of the lost heroes of World War II. The Pentagon still hopes to recover him. Until then, it considers his jungle crash site a sacred place — and the last known clue to finding him. Australian Robert Greinert finds and restores wrecked airplanes. — Globe Staff Photo/Yoon Byun.ALBION PARK, Australia — To the US military, Carter Lutes, a pilot who vanished in Papua New Guinea in April 1944, is one of the lost heroes of World War II. The Pentagon still hopes to recover him. Until then, it considers his jungle crash site a sacred place — and the last known clue to finding him.

Yet while the military was making plans to search for Lutes's remains, other visitors arrived on the site seeking different remains: Lutes's aircraft — a P-47D Thunderbolt, a highly sought-after model in the booming market for authentic World War II planes.

Driven largely by wealthy American collectors, interest in such "warbirds" has grown into a multimillion-dollar frenzy that rivals the most feverish art trend or real estate boom, according to interviews with dozens of collectors, aircraft restorers, museum curators, and government officials.

Now, as the US military invests hundreds of millions of dollars to recover the remains of World War II pilots, it is in a race against relic hunters. In recent years the Pentagon has found nearly 500 missing soldiers from World War II, about half from Papua New Guinea, scene of the most dangerous air battles of the war.

But by the time recovery teams arrive at suspected MIA sites, the locations often have been picked over and crucial evidence is missing.

For example, the P-38 Lightning flown by one of Lutes's missing comrades, John R. Weldon, is now registered to Artemis Aviation Group LLC in Wilmington, Del., according to FAA records. An advertisement published in January said the plane had a "documented combat history with the historic 475th Fighter Group." It was for sale for $495,000. Officials from Artemis did not return calls for comment.

Weldon, who was last seen flying over the eastern coast of Papua New Guinea in January 1944, is still considered a missing soldier, and the Pentagon hopes to recover his remains for a hero's burial.

"We have had to address at least one case that involves this type of site disturbance on every mission that we've done," said Chris McDermott, a historian with the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command. "The salvaging of the plane leaves us with little to go on. The opportunity to evaluate all the evidence has been lost."

Lisa Phillips, head of the Maine-based WWII Families for the Return of the Missing, considers taking the planes to be akin to grave robbing.

"Disturbing an MIA site is devastating to the identification of our war dead," she said. "There is a very systematic way to recover remains and identify them. When individuals disturb a site ... it could ruin all chances of having our missing loved ones identified."

Salvage trumps recovery

A decade ago, a World War II fighter plane could be purchased for a few hundred thousand dollars at most. Now, the price for a restored P-51 Mustang, a sleek single-engine fighter called the "Cadillac of the sky", is increasing by tens of thousands of dollars a month; one was offered last summer for $2.7 million, according to Trade-A-Plane, a listing of aircraft sales.

Prices are even higher for the exotic-looking, twin-engine P-38 Lightning; the last two that exchanged hands reportedly went for a whopping $3.8 million and $7 million, respectively.

To feed the demand, wreck hunters are congregating on Papua New Guinea, where jungles mask hundreds of World War II planes — along with at least 2,200 missing American fliers.

The plane last flown by Lieutenant Marion C. "Carter" Lutes is now the pride of two wreck hunters: Fred Hagen, 51, a Pennsylvania millionaire who became "obsessed" with warbirds after searching for the remains of a pilot who was his great-uncle, and Robert Greinert, 51, an Australian aircraft restorer who proudly displays the shell of Lutes's plane in his workshop south of Sydney.

Sitting on a dolly in a cluttered hangar, the wings, tail, and nose of Lutes's plane are gone, and cables spill from its rusty fuselage. The readings on the cockpit dials that Lutes relied on are frozen behind cracked glass.

"It's neat," said Greinert, wiping grease from his hands and gesturing toward the P-47D Thunderbolt.

For Hagen, a construction business owner who says he paid $100,000 for Greinert's help in the salvage operation, the plane is a treasure.

"It's going to be a work of art," Hagen said in an interview in his stone farmhouse overlooking the Delaware River. "It's going to be a masterpiece of engineering and it's going to be an important historic artifact."

But to Pentagon MIA searchers looking for their "brothers," people like Greinert and Hagen make their mission much harder.

"There is a lot of evidence in there — once you start poking around and moving things, that evidence can be lost or destroyed," said Johnnie Webb, a Vietnam veteran and the top civilian official at the MIA recovery command. "If there are remains in there, they have given their life for this country. We have a responsibility to bring them home."

The Pentagon believes the remains of Lutes, who was a 39-year-old former Firestone clerk from Oklahoma, could still be near the crash site. When military investigators first visited it, they called for an excavation by a forensic anthropologist.

But the anthropologist never got to see the undisturbed site.

Major Brian Desantis, a military spokesman, said Hagen and Greinert persuaded the Papua New Guinea National Museum, which is in charge of protecting the sites, to let them recover the aircraft for salvage, even as the MIA recovery command "tried unsuccessfully to have this blocked."

Islands full of wrecks

Under a blazing August sun in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, three men sat under the wing of a restored P-38 known as "Ruff Stuff."

There was the pilot, the chief restorer, and the man considered the godfather of wreck hunting, a 71-year-old, soft-spoken New Zealander, Charles Darby.

The plane was among the biggest draws at last year's EAA AirVenture, the country's largest gathering of aircraft enthusiasts, with more than 400 warbirds and a half million spectators.

Many trace the modern wreck-hunting trade to Darby, author of a 1979 book, "Pacific Aircraft Wrecks ... And Where To Find Them." It contains dozens of pictures of nearly intact World War II aircraft in Papua New Guinea's fields and jungles. Greinert calls the book his bible.

Darby's father once managed coconut plantations in Papua New Guinea and told stories of islands littered with the wreckage of war.

On Darby's first visit to the islands in 1963, he hunted wrecks. While still a university student, he said, he got a call from an American, asking, "Hey Sonny, I hear you can get me a P-39," an early-war fighter called the Airacobra.

Darby's reply: "I can get you a whole squadron."

So began a series of salvages. In his book, Darby explained how to combine parts of different wrecks to create a complete aircraft.

"So what you do is you get one or two airplanes and you start taking them apart, piece by piece," explained Gerald Yegan, a collector from Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Darby, in an interview, acknowledged finding human remains in some of the planes. Once, when he and his team found a B-24 bomber with the crew and its bombs still inside, they tried to do the right thing, he said. "We got some bones, put them in body bags, called the [New Guinea] authorities."

But the authorities declared the site a danger and blew "the bombs, plane, and rest of the crew to smithereens," Darby said.

Thereafter, Darby said, when his team found planes with remains inside, they simply left them in place.

The greed of the original wreck hunters, however, would eventually upset island authorities. A collector who worked with Darby was banned for life, accused of corrupting officials and stealing national war relics.

But a new generation would take their place, led by Greinert, who is known for traveling deep into the jungle to find the most valuable wrecks, those that were lost in combat.

Pieces with murky origins

One of the planes Greinert pulled out of the jungle was a P-39 Airacobra, serial number 42-66534. According to military records, it was last flown by Lieutenant Charles H. Chapman before it collided with a Japanese bomber on May 18, 1942.

Spotted by local hunters near the Papua New Guinea capital of Port Moresby in 2001, the plane soon came to the attention of the MIA command, which dispatched a local contractor to the site to begin searching for Chapman's remains.

But before an anthropologist could get there, Greinert salvaged the wreckage, according to the military command.

Greinert said he placed the parts from Chapman's wreck in storage at the Papua New Guinea National Museum. Another well-known wreck hunter removed them and shipped them out of the country, according to Greinert and two others who worked with the wreck hunter.

The whereabouts of Chapman's plane could not be confirmed, and some wreck hunters believe that it has been cannibalized for parts — a common occurrence that usually takes place far from the eyes of the rich collectors who fund the warbird trade. The most famous collector in the United States — owner of at least 15 of the most prized warbirds — is Paul Allen, the cofounder of Microsoft and owner of the Seattle Seahawks football team. The most famous collector in the United States — owner of at least 15 of the most prized warbirds — is Paul Allen, the cofounder of Microsoft and owner of the Seattle Seahawks football team.

Allen's collection, envied among warbird enthusiasts, has been restored, in part, by a US-based workshop called WestPac, whose operator, Bill Klaers, told the aviation trade magazine Aeroplane that he receives wrecks from Papua New Guinea. Klaers did not respond to numerous Globe messages.

David Postman, Allen's spokesman, said in a written statement, that "We strongly believe that obtaining information about fallen pilots and crew is far more important than collecting vintage aircraft" and that none of Allen's planes themselves were involved in fatal crashes.

He acknowledged that Allen uses WestPac for parts and restoration, but said: "While we can't know where every part for every aircraft comes from, it is highly unlikely that parts from overseas wrecks of American planes were used in our restorations. There is a readily available supply of authentic but unused parts for vintage American war planes in the United States."

Despite Postman's assertion, numerous wreck hunters and restorers — including Greinert, Yegan, and Allen's own curator, Adrian Hunt — noted in interviews that many types of parts are scarce in the United States and that restorers often rely on New Guinea wreckage, both for the parts and for templates for making replacements.

And critics insist that collectors should make certain that none of the parts come from MIA wrecks, rather than shift the responsibility to their restorers.

"A museum that says, ‘Oh, we don't know where this stuff comes from’, to me, it's a reckless statement," said Justin Taylan, who runs the website PacificWrecks.org. "If it were an art museum or any type of historical entity, that wouldn't fly."

But others make the same contention, including the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum's restoration facility in Maryland. The Smithsonian relies on the workshop at Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, to provide parts for its planes.

Al Bachmeier, museum specialist at the Smithsonian facility, said he does not ask the suppliers to verify the origin of each piece mounted on a Smithsonian display plane.

"Boy, I don't know whether we've asked those kind of questions," he said. "Our biggest problem is monitoring something like that from 3,000 miles away."

Inside Pima warehouses, however, sits a lineup of seven P-47 Thunderbolt fuselages, each wingless, cut off at the nose, and battered — some of the original planes chronicled in Darby's ground-breaking wreck-hunting book, according to museum curator Scott Marchand.

Good deed or greed?

From his office in a run-down industrial park in Port Moresby, John Douglas has had a front row seat to watch the scramble for World War II relics.

An environmental assessor and helicopter pilot, Douglas knows the remote terrain probably better than anyone. He has a card catalog of roughly 600 to 700 World War II aircraft wrecks. Stashed away in his special collection of war memorabilia are the dog tags of dozens of American soldiers.

By the 1990s, he gained a reputation as one of a handful of people who could help enthusiasts find wrecks and negotiate with locals.

Although it is technically illegal to remove aircraft from the island, wreck hunters simply "pay a little grease money to somebody and the container disappears," Douglas said.

"The museum here has policies that say we'll only trade with museums or government to government," he added. "But if somebody turns up with a few donations, a few caps of beer and a bit of loose cash, it's, ‘Yes, whatever you want’."

Simon Poraituk, the director of the cash-strapped National Museum in Port Moresby, calls these payments a "donation."

"It's sort of a donation that was put in, in exchange for taking the aircraft," he said in an interview.

To the US military, however, they are bribes.

Hagen, for his part, maintains that his search for prized aircraft has helped bring answers to families who lost loved ones, such as that of 19-year-old Wilfrid J. Desilets Jr. of Worcester, whose remains he recovered in 1997.

At Desilets's funeral, Hagen spoke at the family's invitation.

He says the US military, with its limited ability to search for the 78,000 personnel missing from World War II, should be grateful for his willingness to invest his money and undertake personal risks to reach some of the wreck sites.

"They need an army of people like me if they are serious about it," Hagen said. Wreck hunters, he added, "shouldn't be excoriated and put down because they've taken the trouble to do something which is very noble."

But the race between the military and the wreck hunters is accelerating, the Pentagon says. Because Papua New Guinea has opened its unexplored terrain to mining, timber, and energy companies, more warplanes are being discovered each week — and many likely contain the remains of their fliers.

If wreck hunters get there first, warned former Navy archeologist Wendy Coble, the crews may never be found.

"Is that fair to the families?" Coble said. "Because somebody decided they wanted to have something to fly?"http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2009/05/25/remains_are_lost_in_race_for_relics/?page=full

|