Kiwithrottlejockey

Admin Staff

XNC2 GOD

Posts: 32250

Having fun in the hills!

|

|

« on: March 12, 2015, 11:48:00 am » |

|

From the Los Angeles Times....To Woodstock, on the ‘Frankly Dankly’ school bus of '69Forty years ago, an oil-dripping heap with the name of a fictitious band

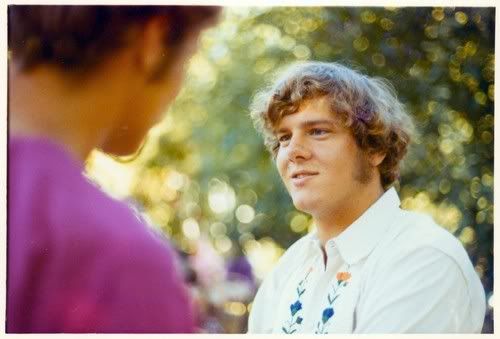

painted on its side took a coterie of young activists to the famed

music festival 40 years ago, and to their own turning points.By PAUL LIEBERMAN | 2:17AM PDT - Saturday, August 15, 2009 Writer Paul Lieberman, shown in 1969, traveled to Woodstock on a bus Writer Paul Lieberman, shown in 1969, traveled to Woodstock on a bus

painted with “Frankly Dankly and his Seven Little All-Americans”, the

name of a fictitious band. — Photo: provided by Paul Lieberman.NORTH ADAMS, MASSACHUSETTS — The statute of limitations should protect us from prosecution, so let the truth be told — we used anti-poverty funds to buy the Frankly Dankly bus in the landmark summer of '69. One of our group still insists we “passed the hat” to pay for the thing. But he's a respectable lawyer now, so we'll allow him that fog of memory. Everyone else is willing to 'fess up that we dipped into money intended to help the poor to procure the oil-leaking school bus we saw sitting in a lot with a “For Sale” sign.

Oh, we had a cover story for spending the $500 — that we could use a roving tutorial center to reach kids beyond the old mill towns where we were soldiers in the war on poverty. We no doubt hoped that would be the fate of the bus, eventually. But first we tore out the seats, painted the sides bright red, white and blue, and etched on the name of a nonexistent rock band, Frankly Dankly and His Seven Little All-Americans. Then we loaded it up with turkeys and pancake mix and headed over the Berkshires to a muddy farmland in Bethel, New York.

We actually had tickets for the three-day Woodstock Music and Art Fair, our coterie of idealistic college students who exemplified an era that blurred the line between political activism and experimenting with new lifestyles. We'd spend days helping low-income families find housing, then gather at night to mull over our motives and shed our inhibitions with encounter groups that left us half-naked on the floor. We would open a community center with a parade down Main Street.

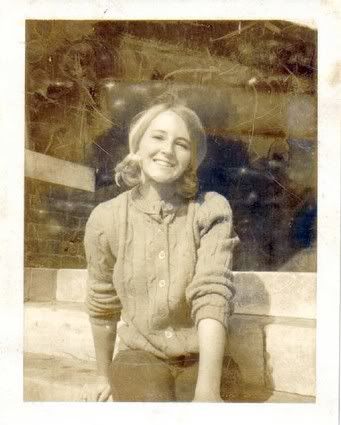

This weekend's 40th anniversary of Woodstock is spawning a new torrent of recollections of that summer that may leave generations born before and after screaming, “Enough!” But trust me, the Frankly Dankly saga is not just another baby boomer nostalgia trip, for from our crew came a movement that's a lightning-rod today. Salli Benedict, the group's “Earth mother” at 21, roasted Salli Benedict, the group's “Earth mother” at 21, roasted

the turkeys that would sustain the festival-goers, who

started the drive to Upstate New York playing Canned

Heat's “Going Up the Country” on kazoos.

— Photo: provided by Salli Benedict.The Office of Economic Opportunity had been established by President Lyndon Johnson to spearhead his Great Society anti-poverty efforts, but President Nixon was skeptical of it and in 1969 put a pair of up-and-coming Republicans in charge. Let's not blame Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, however, for what we did with their money — North Adams, Massachusetts. was far below their radar.

Our adventure began with two fellow Williams College students who had spent time in this community of 18,000 built around a brick factory that once made Civil War uniforms. The southward flight of the textile industry had devastated New England, so a team of 18 was assembled to help out here and in nearby Adams, some with full slots in VISTA (the Volunteers in Service to America), others dubbed VISTA summer associates.

Several of the group had just graduated from college, but two girls from Bennington College were merely through freshman year, and sauntered about in big, floppy hats. I was only a year older but had street cred as a New Yorker who'd marched in my first demonstration while in my mother's womb, though I'd also worked as a riflery instructor, trained by the NRA.

Bill Cummings was the son of a West Point graduate and had married a fellow military brat, Salli Benedict. Bill had become disenchanted with the war after seeing the wounded in a hospital in the Philippines, where his father was based while staging night bombing raids over Vietnam. Chris Kinnell was a lanky basketball player from supposedly laid back Pacific Palisades. Bruce Plenk was a self-described "save the world type" from Utah who believed that a crusade for social change could be waged with “a lightness and fun to it.”

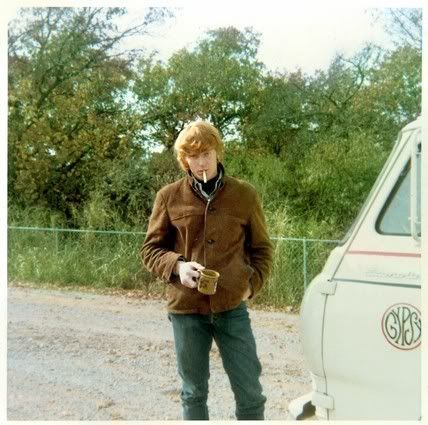

Wade Rathke was not about lightness and fun. The onetime Eagle Scout from New Orleans was, like Cummings, married already at 20. Though he attended the same elite college as us, Wade had supported himself for a time driving a forklift. He had taken a year off to do draft counseling only to become disillusioned when better-off kids were all that came through the door. Now he'd lean silently against a wall at our meetings, a cigarette dangling from his mouth. Community organizer Wade Rathke, who went on to found ACORN, Community organizer Wade Rathke, who went on to found ACORN,

now a lightning rod for conservatives, skipped Woodstock.

— Photo provided by Wade Rathke.Our orientation coincided with a Boston rally of the National Welfare Rights Organization, where we met Saul Alinsky, who had become a legend organizing around the Chicago stockyards. “When you come into a community, you don't have ‘issues’,” Alinsky told us. “You have ‘sad scenes’. Your job is to turn those sad scenes into issues.”

But how many college kids had what it took to go door-to-door in housing projects to persuade welfare mothers to sit in at a government office to obtain back-to-school clothing for their kids? The Welfare Rights honchos saw one candidate in our crowd, Rathke. I think many of us were relieved when he agreed to organize the city of Springfield, an hour southeast of our western Massachusetts towns.

For the rest of us, the work seemed snake-bitten that summer. We spent weeks promoting a meeting of tenants at a church in North Adams only to have astronaut Neil Armstrong pick that night to step on the moon. The two locals who showed up must have been the only ones without TVs. It poured the day we opened the community center in an old supermarket. Still, we danced into the wee hours to a band that did perfect covers of Three Dog Night hits (“One is the loneliest number ...”)and soon would play as a warm-up act at ... well, enter the bus.

Ads for the August 15th-17th Woodstock festival promised “Three Days of Peace & Music”, peace first, music second. The promoters expected 50,000 people for a celebration of an egalitarian spirit with “painting and sculpture on trees [by] accomplished artists, ghetto artists and would-be artists”. But what attracted us were acts such as Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. If purchased well in advance, three-day tickets cost $18, so the Bennington girls collected that and mailed in our money. Cummings floated the idea of buying the school bus a week into August, saying we could reach rural families. That's when I piped up, “Why kid ourselves?” We all knew the real motive. Counterarguments flew back: The bus cost next to nothing. We were paying ourselves a pittance, $25 a week. We could say the $500 was from donations from college alumni, never mind that all our funds were mingled. But I was an effective spoilsport. We voted down the purchase.

Then everyone got drunk, or whatever, and in the morning we bought the bus.

We did paint it off-hours. Then we paid a local sign man to letter on “Frankly Dankly and his Seven Little All-Americans”, a name fellow students used for a phantom band they kept promising would play at parties. We bought sleeveless T-shirts and painted “F.D.” in red on each. Salli, our Earth mother at 21, roasted the turkeys. We took off mid-morning Friday, August 15th, our kazoos playing Canned Heat's “Going Up the Country".

The bus drew stares whenever we stopped, which was at almost every gas station because it wouldn't hold oil — there was a reason we got it for $500. In quaint Millbrook, New York, a couple hurried their children into their car at the sight of our bus. There was a power to the budding Youth Culture, even if it split our society.

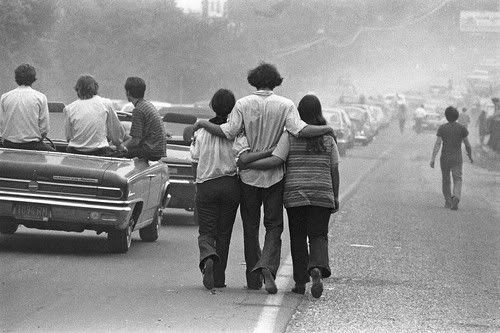

The traffic became inch-along dense miles from Max Yasgur's farm, where the festival would be, but we talked our way through one checkpoint by insisting, “We've got Mr. Dankly's equipment in the back!” Then a second security guy checked, saw only our kazoos, and guided us into a field with two dozen other painted buses. Mud caked the sneakers and moccasins of the thousands of youths in their own floppy hats and painted t-shirts trudging like refugees in a war zone past where cattle had grazed a day before. The traffic became inch-along dense miles from Max Yasgur's farm, where the The traffic became inch-along dense miles from Max Yasgur's farm, where the

festival was held. Thousands of youths headed toward fields where cattle had

grazed the day before, and where artists like Jimi Hendrix and Joan Baez

would make history. — Photo by Baron Wolman.We joined the procession and 45 minutes later heard the dim sound of music. We glimpsed the makeshift towers behind the stage. They'd given up on taking tickets. We were directed up the far side of a hill, sensing the mass of people but seeing little.

Finally, we made a left and took in the spectacle through dimming light: We were halfway up a natural amphitheater that once was an alfalfa field but now resembled a staging ground for the Roman legions. Though we were a quarter mile from the stage, it looked as if every inch was packed, with more people than we'd seen in one place.

Years later, we could not be sure what we witnessed and what we saw in the Woodstock movie. A few of us thought we caught the opening act, Richie Havens, but the first I recall was Country Joe McDonald, doing his anti-war ditty: “And it's one, two, three … What are we fighting for? … Don't ask me, I don't give a damn … Next stop is Vietnam”.

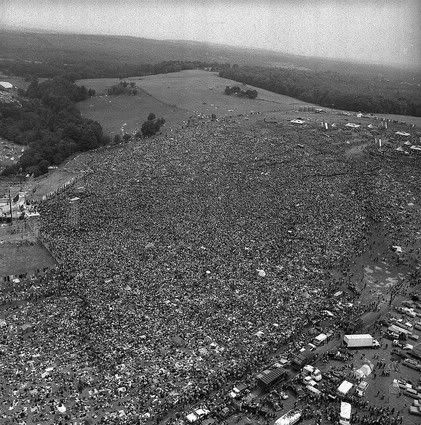

Then I went exploring up the hill and lost our group. The youth culture that had gotten us so much attention en route swallowed me up. After the night ended with Joan Baez singing “We Shall Overcome”. I feared I'd never find the bus, but did, somehow. The next morning, Bill and Salli made pancakes for hundreds of passersby. So the bus did do some good for humanity. The Woodstock festival promoted as “Three Days of Peace and Music” The Woodstock festival promoted as “Three Days of Peace and Music”

drew more than 400,000 people to farm fields. Organizers had

expected closer to 50,000. — Associated Press/August 16th, 1969.Saturday was a wet blur. Someone had to wake Bill so he could hear Sly and the Family Stone. Sunday, we were gone long before Hendrix performed his agonized Star Spangled Banner. We were intent on being at our $25-a-week jobs Monday morning.

Before we knew it, most of us were back at college, but a core stayed in North Adams and engineered one tangible success, construction of low-cost housing. Little was said of the bus, which never made any community rounds. Suffering from a cracked block, it was last spotted in a field, left to rust into oblivion with our memories.

It took work to find some of the crew: Bill Cummings is a PhD ecologist who monitors development projects in Pakistan but lives outside Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Though he's no longer married to Salli, she's there too, directing public health programs, the latest targeting obesity among poor women. They dote on four grandkids and recently took a couple to an outdoor concert by Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson and John Mellencamp.

After years as a legal aid attorney, Bruce Plenk coordinates solar energy projects for the city of Tucson. Our basketball player from Pali high, Chris Kinnell, is a minister in upstate New York, just back from a mission to Zimbabwe. The guy who swore we passed the hat to buy the bus, John Kitchen, is a lawyer who works with the disabled in New Hampshire. One of the Bennington girls became a psychologist.

Wade Rathke, in contrast, was a snap to find. He's been living what he calls his “Britney Spears moment” since the presidential race that put Barack Obama, a onetime community organizer, in the White House. That's when the organization Wade founded, ACORN, hired 8,000 canvassers to register 1.3 million voters. Backers of Senator John McCain accused it of trying to steal the election.

Wade never did return to school that fall of '69, but the local papers reported his progress in Springfield, where he led hundreds of welfare mothers demanding vouchers for winter coats. He was thinking of returning south to establish “a strong conflict group,” concentrating on poor whites. Then he was gone, to Arkansas, to launch the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now.

Nowadays, he's a favorite villain of the right. “I'm not surprised that I'm seen as a dangerous dude,” Wade said when we reconnected for the first time in four decades. “In fact, I am.”

I asked him about his bid to organize “the rest of the planet”, as one report put it, but I mostly wanted his explanation for missing the Frankly Dankly bus. “Knew about the bus,” he replied. “We had seats on the bus.”

It seems his wife, Lee, (now his ex) had been intent on going with us and shelled out $36 for two sets of tickets, but Wade was not going to be diverted from his Welfare Rights work. Yet over the years his memory combined the summer's events into a semi-fable that had Woodstock weekend as the turning point in his life. The tale had him driving his Ford Econoline van to meet us only to have it break down, so he hitched instead to Springfield and resolved to become an organizer.

“Who knows where I would have wound up if I had gotten on the bus with you guys,” he said. “I might have thought I had a future shaking a tambourine in a rock 'n' roll band.”

The summer of '69 was a turning point for me, as well. I found I was a pretty good observer and, perhaps, had a conscience. Later, when I gravitated to investigative reporting, and projects on working conditions and healthcare, I thought of Saul Alinsky's exhortation to turn “sad scenes” into issues. But I was pulled toward entertaining people, as well, and thought of our embrace of lightness, a quality often overwhelmed by the meanness of today.

My wife and I go to the Berkshires each summer, and North Adams is a regular stop, for the factory that made Civil War uniforms has become a great museum, MASS MoCA. I take back roads, indulging the fantasy that I'll spot kids playing in a patch of high grass, in the corroded hull of vehicle with a trace of odd lettering on its side.http://www.latimes.com/news/la-na-woodstock15-2009aug15,0,4479312.story

|